The Man Who Kept Stretching

It's not unusual for an entrepreneur to sell a company, wait the required non-compete period, and then start up virtually the same company all over again.

It's not unusual for an entrepreneur to sell a company, wait the required non-compete period, and then start up virtually the same company all over again. But when inventor and entrepreneur Ted Coburn, an undisputed master of oriented films, leaves a company or sells a 911±¬ÁĎÍř, he leaves his patents and inventions behind. When he starts a new venture, it's invariably with a new set of patents and concepts, which literally and figuratively stretch beyond his previous work.

Coburn has gotten six patents on film orientation, and has three more pending. His first patent dates back to the 1960s when he worked at Marshall and Williams in Woonsocket, R.I. As an engineer in his twenties, he invented single-short-gap orientation, which M&W still markets.

In 1972, Coburn set out with two partners to start a processing 911±¬ÁĎÍř called Trea Industries Inc. in North Kingstown, R.I. For a year, he kept a day job at Marshall and Williams while designing his own orienting machine to be built by M&W for his new company. Trea developed mono-axial (machine-direction) and later biaxial orientation processes for heavy-gauge (6-mil) polypropylene, pulling it into high-strength films for tape, electronics, and graphic arts. Videos became a big market, and Trea developed the embossed overlay film for video boxes.

In 1985 the partners sold Trea to Toray Plastics, which wanted a U.S. manufacturing presence. Coburn stayed on four more years and then retired. For five years he coached kids' football teams and played with his grandchildren and great grandchildren. He won a Federal Trade Commission lottery for a cell-phone license in Maine and started a 911±¬ÁĎÍř called Cell One, which later became Cingular One. But he still missed stretching plastic.

Orienting heavier film

Ten years ago, he and Robert Papa, both former partners at Trea and colleagues at Marshall and Williams, started Trico Industries Inc. in North Kingstown "as kind of a retirement project," Coburn says. Trico makes machine-direction-oriented (MDO) and unoriented films. The facility was designed for R&D and for versatility to run a range of products. It has blending and compounding capabilities and proprietary software for winding and for die-lip heat control to eliminate gauge bands on rolls.

Unlike his earlier venture, Trico orients heavier gauges. "Where Trea went up to 6-mil oriented film, we go up to 10-mil," Coburn explains. "The goal is to take polyolefins and make them softer or stiffer as alternatives to rigid and plasticized PVC and cellulose acetate." But he cautions that thick MDO film still isn't a large market. Trico usually runs only five days a week, but around the clock on those days.

Trico bought a patented technology called Enviroplast (from a now defunct Canadian firm) for a polyolefin composition that can be RF and ultrasonically welded, unlike most polyolefins. That makes it more competitive for replacing PVC.

Trico is also developing unique formulations based on combinations of incompatible materials. A PS/PP interpolymer, for example, is aimed at PVC replacement. "The materials don't like each other, so when oriented, they cavitate and become opaque," Coburn notes. Trico has three provisional patents pending on applications for this material, which can be RF welded.

Trico is also working on orienting monolayer structures with an incompatible additive to impart specific properties like printability when the additive blooms to the surface. This is an alternative to coextruding a printable surface layer on label stock, which is patented by Avery Dennison.

In addition, Trico is developing monolayer structures that orient at higher temperatures and with less shrinkage than coex films. "Nothing curls, nothing separates," says Coburn.

The company has six new monolayer MDO films in development that should be commercial this year. "First we get patents on a concept. Then it takes a while to learn how to make it on a production basis," Coburn explains. "It takes even more time to convince people to buy it." If even one of the new films catches on, Trico will be the only company in the world that can make it.

Related Content

Shredding Thin Film: How to Do It Right

While many processors recoil at this task, a little know-how in shredding equipment, processing, and maintenance should add the necessary confidence.

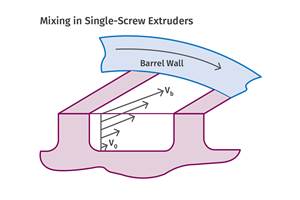

Read MoreSingle vs. Twin-Screw Extruders: Why Mixing is Different

There have been many attempts to provide twin-screw-like mixing in singles, but except at very limited outputs none have been adequate. The odds of future success are long due to the inherent differences in the equipment types.

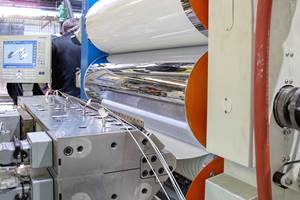

Read MoreHow to Select the Right Cooling Stack for Sheet

First, remember there is no universal cooling-roll stack. And be sure to take into account the specific heat of the polymer you are processing.

Read MoreRoll Cooling: Understand the Three Heat-Transfer Processes

Designing cooling rolls is complex, tedious and requires a lot of inputs. Getting it wrong may have a dramatic impact on productivity.

Read MoreRead Next

Beyond Prototypes: 8 Ways the Plastics Industry Is Using 3D Printing

Plastics processors are finding applications for 3D printing around the plant and across the supply chain. Here are 8 examples to look for at NPE2024.

Read MorePeople 4.0 – How to Get Buy-In from Your Staff for Industry 4.0 Systems

Implementing a production monitoring system as the foundation of a ‘smart factory’ is about integrating people with new technology as much as it is about integrating machines and computers. Here are tips from a company that has gone through the process.

Read MoreSee Recyclers Close the Loop on Trade Show Production Scrap at NPE2024

A collaboration between show organizer PLASTICS, recycler CPR and size reduction experts WEIMA and Conair recovered and recycled all production scrap at NPE2024.

Read More